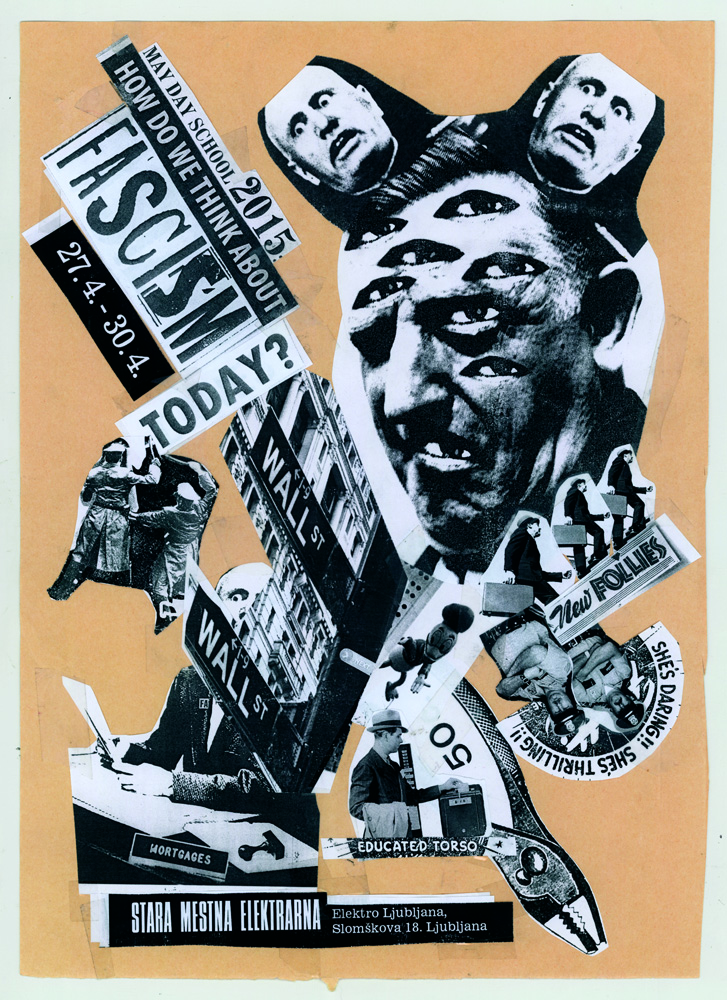

How Do We Think About Fascism Today?

Ever since the rise of Italian fascism and German Nazism in the first part of 20th Century and up till today the term fascism comprised the terminological core of left-wing (especially socialist) theoretical and political projects. In the first part of 20th century this term was used to characterize both Italian and German regimes or even any regimes and movements that mimicked German Nazism or Italian fascism. On the political front the term was used as a swearword, which is why its use probably expanded as much as it did. With regards to this it is instructive to remember Stalin, who angrily denounced social democracy as but the “moderate wing of fascism”. The concept of fascism thus rapidly lost its analytical value: it was either used as such an abstract concept that it could cover an unlimited amount of political actors or phenomena, or it stifled a sober-minded reflection and evoked primarily emotional responses with its denunciatory tone.

Contemporary revivals of the concept are faced with much the same problems. Michel Foucault’s discovery in the 1960s of “everyday life fascism” is a symptomatic example. Foucault’s reconceptualization of fascism strove to shift the analytical focus from big political personalities, parties, movements and regimes of the early 20th Century towards the “tyrannical bitterness” of our minds, and actions that endow us with the lust for power and domination. What Foucault’s discussions of fascism usually chipped away at was the “Old Left”. The latter prided itself on its tradition of antifascist struggles, but it was blind for both the authoritarian and chauvinistic tendencies in its own ranks, as well as for the mechanisms of segregation and stratification that were constitutive of the “welfare state”. However, wasn’t Foucault’s conceptualization embroiled in the same dilemmas as was its subject of critique? It seems that Foucault’s all-encompassing understanding of fascism was indicative of the same abstractness of the concept, which can be used to subsume every disliked mechanism of power or relation of domination. It is, therefore, not unusual that not even this conceptualization is able to discriminate between fascism and social democracy.

On the one hand we seem to be faced with the rather abstract notion of fascism which is able to subsume every phenomenon, thanks to its vagueness and generality. Yet on the other hand we have the concept of fascism that is historically and geographically very firmly situated. In this latter sense the term is used extremely narrowly – it is used to characterize the two infamous regimes that existed in Germany and Italy in the first part of 20th Century. This is, of course, a much more clear definition which also avoids some of the trappings of abstract conceptualizations. However, it is not any less problematic because of this. It is usually used by contemporary bourgeois historians or ideologues who try to depict fascism as nothing more than a tragic eccentricity long past; an eccentricity that managed to temporarily disrupt the otherwise smooth and balanced flow of modern capitalist societies, which are resting on perfectly healthy foundations. In such hagiographical musings fascism is always depicted as something completely external to bourgeois society. This helps to ideologically entrench its pristine veneer. Effectively, it tells a tale of German Nazism and Italian fascism as a mysterious eruption out of nowhere, not as something that is born out of the tendencies, contradictions and antagonism that are basic to bourgeois societies of our time. In tales of the first kind fascism is presented not as an actual internal threat, but as something completely contingent and external.

How do we, in light of these dilemmas, think about fascism in the context of contemporary socio-political situations? Our social context is characterized primarily by the long-term effects of the global capitalist crisis that easily rival those of the Great Depression from 1929. Our current-day situation is, therefore, in some respects similar to the historic situation that gave birth to fascism in the first part of 20th Century. In Europe we are witnessing the electoral rise of right-wing parties with extremely reactionary, racist, xenophobic, chauvinist and anticommunist rhetoric. But the strengthening of racist and xenophobic tendencies is not limited only to rhetorical tropes of right-wing politicians. These tendencies are institutionalized in the formal migrant and asylum policies of the EU and its member states. The implementation of austerity measures and “structural reforms” is backed up by authoritarian methods and a pretty drastic narrowing of the mechanisms of parliamentary democracy. Political decision are becoming more and more the monopolized privilege of narrow experts nobody voted for, while the rebelling masses of people are met with intense state repression. It is not even unusual, in such cases, for the most eminent European politicians to resort to defamatory racist rhetoric about lazy hedonist people of the Mediterranean and the need to let go of our social and political rights in the name of a return to higher values. It is not unsurprising that such climate gives rise and credence to parties that explicitly mold themselves on the basis of historical fascism – parties like the Greek Golden Dawn, Hungarian Jobbik and Ukrainian Svoboda.

Is any of these tendencies evidence that our contemporary bourgeois societies are becoming fascist? Is the fascist threat today hiding in the political regimes, parties and movements that are reminiscent of historical fascism both in their symbols and rhetoric, as well as their actions? Or is fascism to be traced to structural tendencies, contradictions and antagonisms that are at the root of contemporary capitalist societies? To properly address these questions we first have to ask what fascism even means. What is it, what are its socio-economic, political, ideological and historic characteristics? Only then can we answer the question of what, if anything, is fascistic in our contemporary societies.